An airplane needs three things to operate– fuel, air, and money. A carburetor can help with the first two! How does a carburetor work? Today we are going to learn how an airplane carburetor works, the different types of carburetors, what the carburetor heat does, and good practice tips.

How Do Carburetors Work?

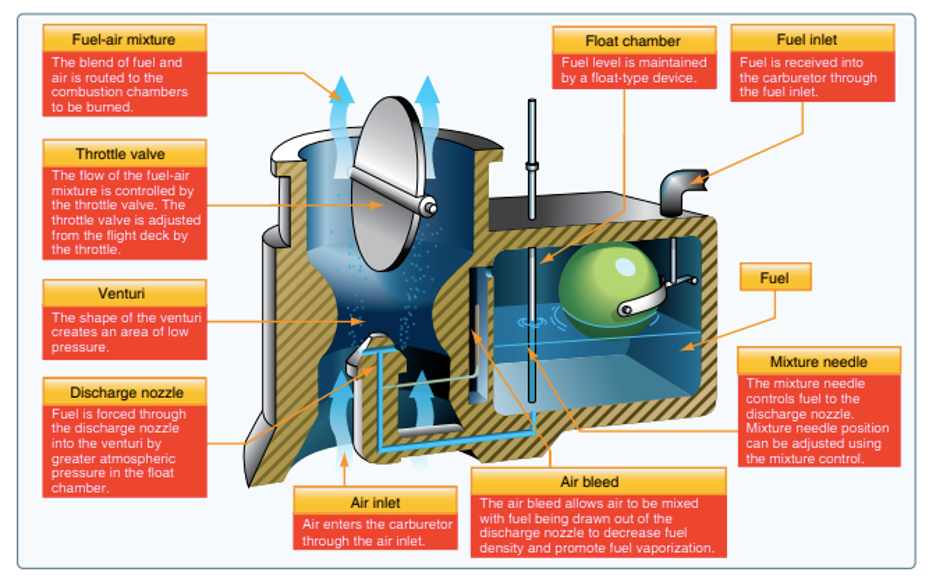

The carburetor forms the engine’s induction system and is responsible for mixing air and fuel. The mixture is then fed to each cylinder in the engine where it is ignited to generate power.

A carburetor does this by use of what’s called a venturi. A venturi is nothing more than a tube where the middle section is indented. This creates an area of decreased air pressure and increased air velocity. Fuel is then shot up through the middle of the carburetor venturi and mixes with the air. Because the air within the venturi is at a lower pressure than the air around it, it creates a vacuum that draws fuel out of the main discharge nozzle. It is fed into the engine’s cylinders during the intake stroke. The amount of fuel to be put into the mixture is controlled by your mixture lever in the cockpit. The amount of total fuel/air mixture fed to the engine is controlled by the throttle in your cockpit.

Confused yet?

That’s ok. This is a very difficult topic to visualize. Thankfully, Angle of Attack’s Private Pilot Ground School has you covered. Angle of Attack’s Ground School is made for the visual learner. Our program contains simple, yet effective, graphics that help the non-engineer and the NASA systems officer alike understand concepts like this. Check out our program for an even better understanding of the Carburetor system.

What Type of Carburetor is Used in Aircraft?

Aircraft carburetors are divided into two categories:

-

float-type carburetors

-

pressure-type carburetors.

A float-type carburetor is the most common of the two. Pressure-type carburetors are usually not found on small aircraft. The basic difference between a float-type and a pressure-type carburetor is how each delivers fuel. The pressure-type carburetor delivers fuel under pressure by a fuel pump.

A float-type carburetor uses–you guessed it–a floating bopper to maintain a proper fuel level. The float measures the amount of fuel entering the carburetor, depending upon the position of the float, which is controlled by the level of fuel in the float chamber. When the level of the fuel forces the float to rise, the needle valve closes the fuel opening and shuts off the fuel flow to the carburetor. The needle valve opens again when the engine requires more fuel. The flow of the fuel-air mixture to the combustion chambers is regulated by the throttle valve, which is controlled by the throttle in the flight deck. Float-type carburetors are not just used in aircraft, they are even found in your lawnmower.

What does Carburetor Heat do?

One of the first experiences students have with the carburetor is the carburetor heat lever in the cockpit. The “Carb Heat” is an important part of the operation of the engine as a whole. Carburetors are notoriously fickle. They are susceptible to a number of issues, but one looms large over all others–icing.

An aircraft will show a gradual decrease in engine RPM, and perhaps run rough, when carburetor ice has formed. If the icing becomes severe enough it can “starve” the engine of the mixture it needs to operate thus causing the engine to quit. This is a gradual process, thus it can be very difficult to detect.

By now you might be wondering–how in that big hot engine full of movement can ice form? Well, remember that venturi thing? How in there, the pressure decreases and velocity increases? Another byproduct of that venturi effect is a drop in temperature that can create icing. This icing can occur at any outside air temp, but it’s most likely to occur when the outside air temp is below 70 degrees and the relative humidity is above 80%.

By now you might be wondering–how in that big hot engine full of movement can ice form? Well, remember that venturi thing? How in there, the pressure decreases and velocity increases? Another byproduct of that venturi effect is a drop in temperature that can create icing. This icing can occur at any outside air temp, but it’s most likely to occur when the outside air temp is below 70 degrees and the relative humidity is above 80%.

To combat carb icing the carb heat draws heat from an area near the exhaust and redirects it to the carburetor’s venturi. This rise in temperature ensures ice does not form. Carb heat can be used to melt ice that is already formed in the carburetor so long as the accumulation is not too great. However, using carburetor heat before ice forms is a better tactic. You might notice that some more complex aircraft, don’t have a carb heat lever. This is because those are fuel-injected engines. Fuel-injected engines are not as easily prone to icing.

Where Did The RPM’s Go?

You might be wondering why in your run-up, or in the air, anytime you apply carb heat there is a slight drop in RPMs. The answer to this comes back to a basic concept you might have learned in the “weather” section of our Private Pilot Ground School. Recall that warmer air is less dense than cooler air. When you apply carb heat you are now supplying the engine with warm air instead of cold air, thus decreasing performance slightly. Remember, a slight decrease in RPM with warm air pales in comparison to the RPM drop you will have with an iced-over carburetor.

It’s good practice to cycle the carb heat every so often during your flight. As a practical point, I do so every 20 minutes of a flight and/or anytime there is a change in the flight parameters (i.e. an altitude change, entering a pattern, etc.). Check your POH/ checklist for what your manufacturer recommends. Anytime you mess with the fuel and engine it is a good idea to have an emergency spot to land picked out– just in case.

Carburetors are difficult things to learn about, especially if you don’t have much mechanical experience. Angle of Attack strives to make the learning process easier. Our program’s layout and visual tools can make learning the nuances of this complicated device simple. Learn the basics of aircraft mechanics before you hop in. Check it out today!

Michael Brown grew up flying on the banks of the Tennessee River in Chattanooga, TN. He obtained his private pilot’s license in high school and has instrument and seaplane ratings. Michael graduated from Texas Christian University, where he founded the school’s flying club, with a double major in Business and Communications. He is currently a law student at Tulane University, studying transportation law. Michael was named the Richard Collins Young Writing Award winner and has had his legal writing recognized by the American Bar Association’s Air & Space Subcommittee. When he is not flying or studying, Michael enjoys riding his bike and cheering on his Atlanta Braves.

Stay Connected

Be the very first to get notified when we publish new flying videos, free lessons, and special offers on our courses.