Piloting an aircraft is not challenging once you get the basics right. And one of aviation’s basic concepts is airplanes’ left-turning tendencies. Instructors spend a great deal of time educating the concept of left-turn or yaw to students. Basically, they’re trying to explain why a plane pulls left during takeoff and how to deal with it. Whether you’re new to the concept or need more clarity on it, this article will help.

Here we explain the four left-turning tendencies, why they happen, and what newbie pilots can do about them.

What Are The Left-Turning Tendencies?

Left-turning tendencies arise because of aerodynamics principles. Also known as yaw, it causes the aircraft to drift left. Pilots need to be aware of this phenomenon and adjust the rudder to balance things.

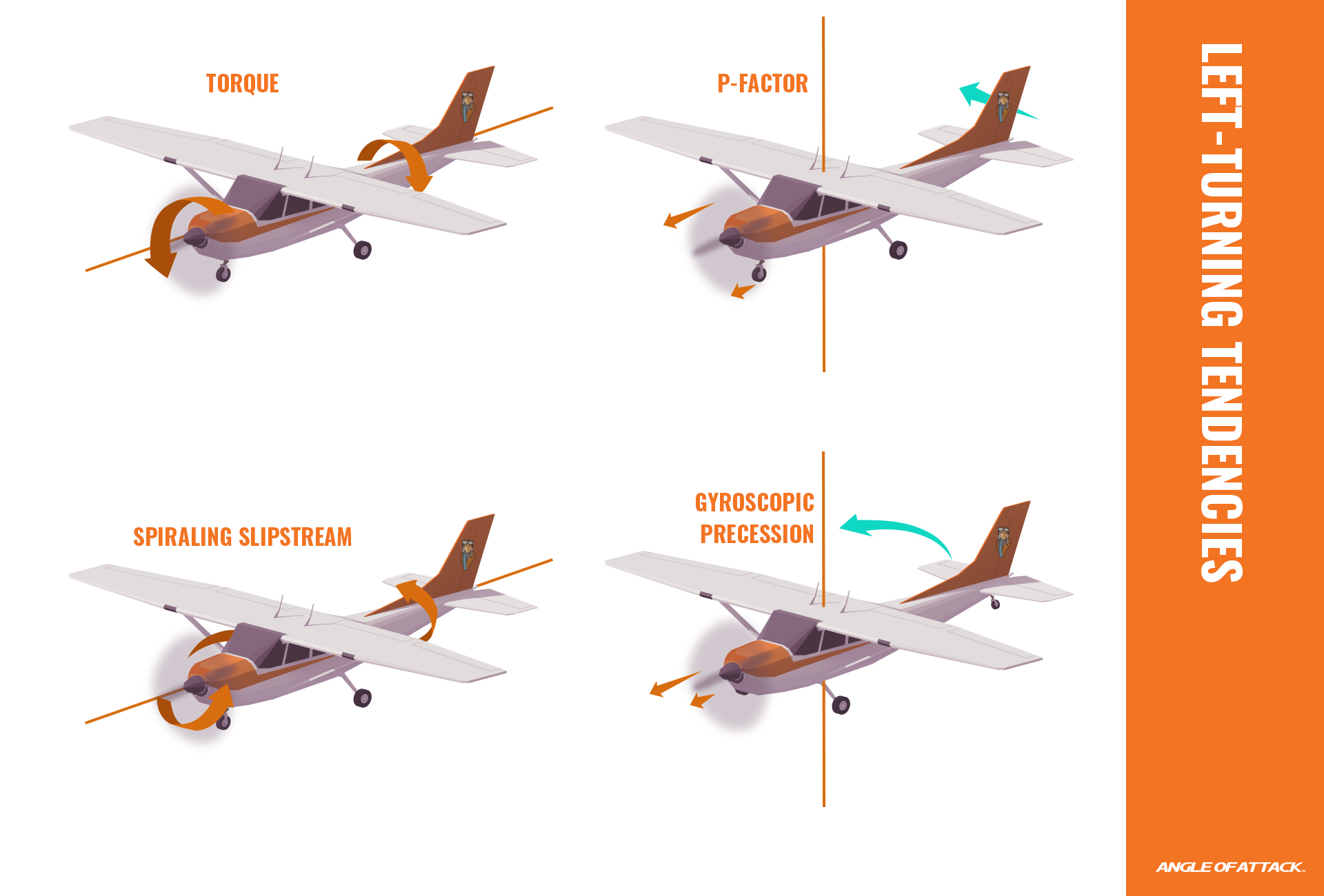

There are four left-turning tendencies of an aircraft, which are:

- Torque

- Slipstream

- Gyroscopic Precession

- P-Factor

Let’s understand each left-turning tendency in greater detail.

Torque

Of all the four tendencies, Torque is the easiest to understand and counter. For that, let’s recall Newton’s third law. The third law of Sir Isaac Newton states that ‘for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.’ For example, let’s say you pull a string outwards. When you do that, an equal amount of force is generated that restores the string to its original form.

The same phenomenon is observed in airplanes. The propeller in most single-engine airplanes rotates clockwise. This clockwise movement generates an equal force in the opposite direction. This causes the aircraft to move left during flight. On the ground, the left-turning tendency generated by torque increases friction on the left side of the landing gear. It also causes the plane to yaw left.

To counter torque, pilots need to use the right aileron input.

Spiraling Slipstream

Slipstream is how the air spirals around the plane behind the propeller. This corkscrew pattern impacts the vertical stabilizer (also known as the rudder) on the left, thus creating yaw to the left. This left-turning tendency is more noticeable during takeoff when the speed of the propeller is faster than the speed of the plane. The air spiraling through the aircraft’s body is more than the airflow over the vertical stabilizer.

The tendency reduces gradually as the aircraft gains speed and total airflow increases. It negates the spiraling air. To counteract this effect, pilots need to be vigilant during takeoffs. Otherwise, the airplane can veer off track. Using the right rudder is the foremost thing to do. When power increases for takeoff, pilots must apply the right rudder input.

Gyroscopic Precession

All rotating objects (even the earth) experience a change in the orientation of their rotational axis. This phenomenon is precession. The aircraft’s propeller is no exception to this occurrence. If you take a gyroscope and spin it, you’ll notice it has two properties similar to that of an aircraft propeller. These are rigidity in space and precession. Thus, the precession observed in propellers is called ‘Gyroscopic precession.’

Now let’s understand how precession affects the propeller. When you apply a force to a rotating object, the effect is felt at 90 degrees in the direction of the rotation. In other words, when force is applied at the 12 o’clock position, the plane will feel a force at 3 o’clock position. This is provided the propeller is rotating clockwise. This causes the plane to turn left. Gyroscopic precession is only significant during takeoff. When the aircraft’s tail rises, the force generated is felt at the top of the propeller.

To counter this effect, pilots are instructed to anticipate the left movement and increase the right rudder input. Gyroscopic precession also occurs during flight, and the aircraft may yaw in the air. Pilots must counter it as well.

P-Factor

The fourth and last left-turning tendency of an aircraft is P-Factor. Also known as asymmetric propeller loading, it occurs when the thrust produced by the propeller is not constant. This results in the aircraft turning in a particular direction, not necessarily left.

In the case of propeller-driven aircraft, P-Factor becomes prevalent when the blade descends.

As already mentioned, the propeller rotates clockwise. This means the blade always descends on the right while ascending on the left. The descending blade creates more lift. Hence, the total lift doesn’t get centered on the propeller arc. Because of this, the lift is offset to the right and the aircraft yaws to the left. P-Factor is more noticeable at higher angles of attack. Slow flight and takeoffs are prime examples of it. To counter this left-turning tendency, pilots input the right rudder to maintain attitude.

Do Jets Have Left-Turning Tendencies?

Jets do not have propellers at the front. So not all of them have left-turning tendencies. That being said, some jets do experience yaw. It depends on how and in which direction the propeller is turning. American jets have propellers turning clockwise, while British jets turn counter-clockwise.

Jets do not have propellers at the front. So not all of them have left-turning tendencies. That being said, some jets do experience yaw. It depends on how and in which direction the propeller is turning. American jets have propellers turning clockwise, while British jets turn counter-clockwise.

The rotating parts and turbines also create the gyroscopic effect, thus causing the jet to yaw. But the modern jets are powered by flight control software that does the heavy lifting. They compensate for the yaw by automatically inputting the necessary rudder.

What Causes P-Factor?

P-Factor phenomenon occurs when the descending blade takes in more load than the upgoing blade. It can happen in two scenarios:

- The aircraft is taking off or in slow flight, where the AOA (angle of attack) is higher

- The plane is a tailwheel airplane

The higher AoA creates more thrust (or lift), thus yawing the aircraft to the left.

What is P-Factor?

P-Factor is an aerodynamic phenomenon experienced by moving propellers at a higher angle of attack. In such scenarios, the location of the center of the thrust changes. It forces the aircraft to yaw to the left. Pilots have to input the right rudder to counter this left-turning tendency.

So, here you go. Left-turning tendencies are generally felt more in single-engine aircraft than in non-conventional multi-engine. This is mainly because of the counter-rotating propellers in the latter that limit the impact of the left-turning tendencies to a reasonable extent.

Nevertheless, as a pilot, it’s crucial that you understand and anticipate these four left-turning tendencies to avoid landing in an uncomfortable situation. In the worst of scenarios, your aircraft may even change its altitude. To learn more about left-turning tendencies, check out our Private Pilot Online Ground School to get more in-depth learning on the topic.

Karey grew up and obtained her in private pilot’s license in Central Iowa. She fell in love with tailwheel aircraft during her primary training and obtained a tailwheel endorsement the week following her private pilot checkride. She is eager to obtain her seaplane rating and is merging her passion for flying with her prior work career. Karey has a background in marketing, editing, and web design after graduating from Simpson College. When she is not flying or working, Karey enjoys anything related to technology and admits she can be a bit of a nerd. She also has discovered a love for virtually all outdoor pursuits, with a special fondness for climbing, shooting, and hiking.

Stay Connected

Be the very first to get notified when we publish new flying videos, free lessons, and special offers on our courses.